Once again, the Brock University Film Society operated as a monthly series during the 2023-2024 season.

Our line-up consisted of the following nine films:

Perfect Days—Thursday, April 11, 2024, 7:00 pm @ the Film House

Wim Wenders began his career as a filmmaker in the late 1960s in West Germany, where he quickly became a leading figure in the New German Cinema movement of the 1970s and 1980s, along with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Margarethe von Trotta, and Volker Schlöndorff. Films like The Goalkeeper’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1972), Alice in the Cities (1974), Kings of the Road (1976), and The American Friend established Wenders’s reputation as director with a particularly sensitive understanding of West German culture and its ambivalent relationship with American culture. These films also brought Wenders widespread acclaim on the international art house film circuit.

Wenders reached directorial superstardom in the 1980s with films like Paris, Texas (1984) and Wings of Desire (1987). The former, which starred Harry Dean Stanton and Nastassja Kinski, captured Wenders’s fascination with America, with American stories, with American landscapes, and with American music (especially the country blues stylings of Ry Cooder) at its strongest yet. The latter, which starred Bruno Ganz (one of the stars of the New German Cinema) and the newcomer Solveig Dommartin, alongside a particularly memorable turn from Peter “Columbo" Falk, playing an unnamed American film and television star much like himself, was one of the definitive portraits of the divided city of Berlin in the period immediately preceding the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It was during this era—the 1980s—that Wenders began to make documentaries with frequency. He would go on to make such celebrated documentaries as The Soul of a Man (2003), about the blues, Pina (2022), a highly ambitious 3D film about the dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, and The Salt of the Earth (2014), a powerful film about the famed Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado, but his most famous nonfiction film was Buena Vista Social Club, the behind-the-scenes story of how the beloved Cuban jazz all-stars album was orchestrated and recorded by Ry Cooder, and then taken on tour to perform before adoring audiences in Europe and America.

The documentary that is most relevant here, however, is Tokyo-Ga (1985), a film about Wenders’s love affair with Tokyo, but especially about his love affair with the Japanese auteur Yasujiro Ozu, whose subtle, measured treatment of contemporary life in the Japanese capital in films like Tokyo Story (1953) was such an inspiration for Wenders and others.

Now, with his latest film, Perfect Days, Wenders has returned to Tokyo to tell a tale of contemporary Tokyo that focuses on a particularly humble, diligent, kind-hearted, and enlightened Tokoyite, played by Koji Yakusho. The role won Yakusho the Best Actor Award at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival. It is exactly the kind of subtle, nuanced role that Ozu would have appreciated greatly.

The Zone of Interest—Thursday, March 7, 2024, 6:30 pm @ the Film House

Like so many directors of his generation—David Fincher, Michel Gondry, Spike Jonze, Sofia Coppola, and others—the British director Jonathan Glazer specialized in music videos early in his career. He’d actually gotten his start in theatre, but when he switched to motion pictures, it was through commercials and music videos for bands like Radiohead, Massive Attack, and Blur that he made a name for himself.

By the year 2000, Glazer had transitioned to feature filmmaking, and he did so in audacious fashion. His first film was Sexy Beast, an outrageous heist film starring Ray Winstone and co-starring Ben “Gandhi” Kingsley as an unhinged sociopath. The film was notable for its settings—Spain’s Costa del Sol and London—and for Winstone’s brilliant spin on the retired ex-con who gets pulled in for “one last job,” but it was Kingsley who stole the show, and who secured a nomination for Best Supporting Actor at the Academy Awards for his performance.

Since then, Glazer has only directed films intermittently, but when he has, he’s tended to make waves. Take Under the Skin (2013), for instance, an odd, fascinating sci-fi film starring Scarlett Johansson. In essence, this was a film in that “sexy alien comes to Earth and wreaks havoc” vein, but it played like Roger Donaldson’s Species (1995)* meets Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), with maybe a pinch of Ken Russell and a little Danny Boyle thrown in for good measure.

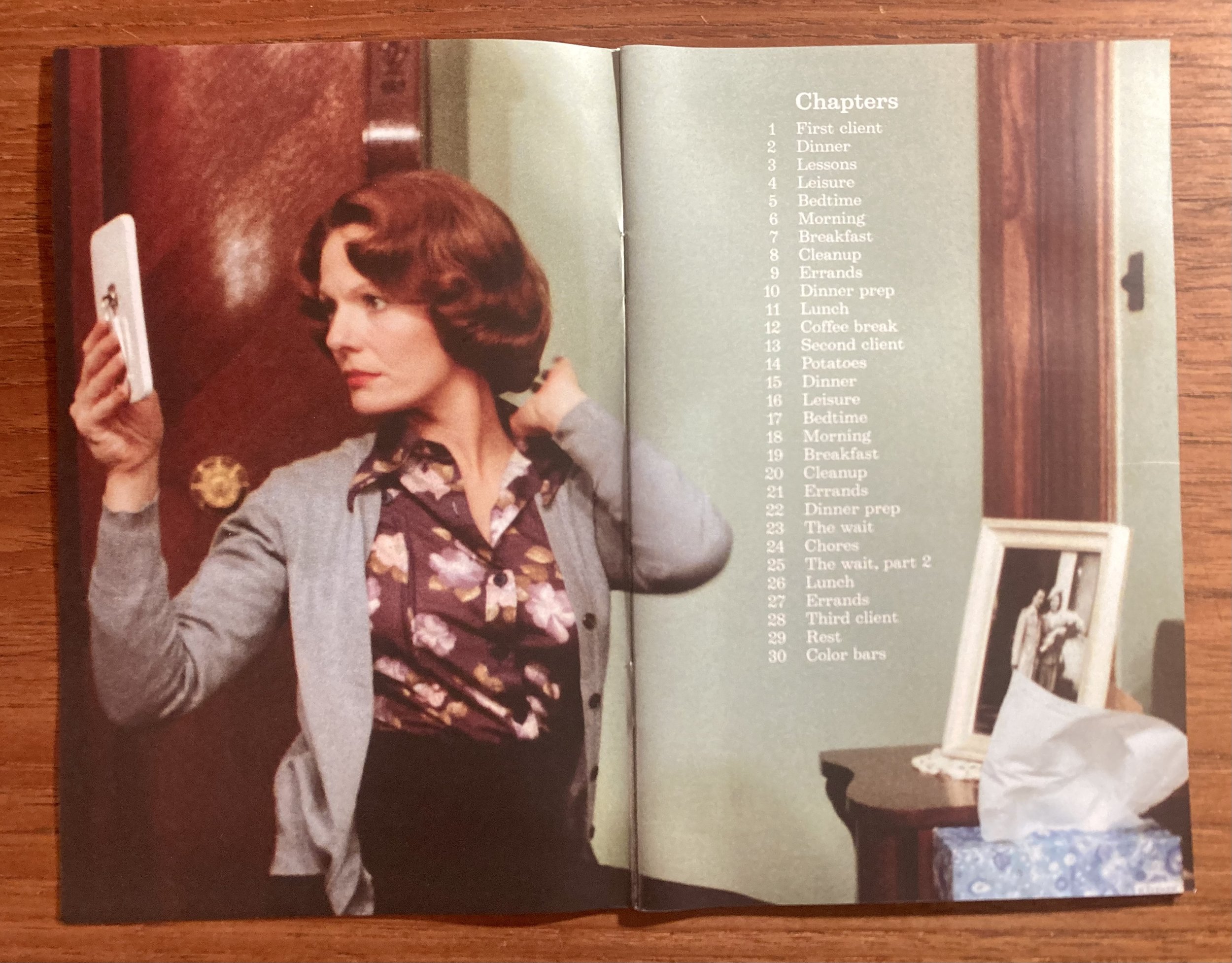

This time around, Glazer has made one of the most acclaimed and controversial films of the year. Based loosely on the novel of the same name by Martin Amis, The Zone of Interest is an ambitious and highly unusual film about the atrocities of the Nazi regime. It focuses almost entirely on the family life of Rudolf and Hedwig Höss—he, the commandant of Auschwitz; she, the hausfrau who cultivated her domestic ideal directly adjacent to the notorious concentration camp. As Ann Hornaday of the Washington Post has argued, the experience of The Zone of Interest is one of watching two films simultaneously: one dealing with the banality of evil that is the Höss household; the other, made up of images conjured in our minds, knowing full well the scale of the crimes taking place on the other side of that wall.

Glazer has picked up awards for The Zone of Interest at both the Cannes Film Festival (where it won two major prizes) and the BAFTAs. It has been nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best International Feature, Best Director, and Best Film.

*Improbably, Ben “Gandhi” Kingsley appeared in Species, too (but not in Species 2).

Anatomy of a Fall—Thursday, February 8, 2024, 6:30 pm @ the Film House

Justine Triet’s star had been steadily rising for about fifteen years, but it reached new heights last May when her latest film, Anatomy of a Fall, took the top prize at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Anatomy of a Fall is part court procedural, part murder mystery, and part contemporary family melodrama—the latter featuring a depth and intensity reminiscent of the work of Ingmar Bergman, and a concern with technology and memory that we might find in an Atom Egoyan film. But it is Sandra Hüller’s fascinating and mystifying performance as Sandra Voyter, a talented and successful novelist who is accused of the murder of her husband, that has electrified audiences.

Indeed, if it’s been a big year for Triet, it’s also been a momentous one for Hüller. Anatomy of a Fall is nominated for Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards, and Triet is also up for Best Director. Hüller, in turn, is nominated in the Best Actress category for her performance in Anatomy of a Fall, but she also stars in Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, another film that has received nominations for Best Picture and Best Director.

One of the themes explored in Anatomy of a Fall has to with the writing of fiction, and where the material that a writer turns into fiction is actually drawn from. Are Voyter’s novels direct reflections of her personal life? Can clues to the truth behind her marriage and her husband’s untimely death be found in her books? What is the stuff of fiction, and how incriminating is it? It’s a theme Triet has explored elsewhere in her work. In fact, she even did so in a film that co-starred Hüller—Sibyl from 2019. In that film, it was a psychotherapist-turned-novelist (played by Virginie Efira) who was basing her novels directly on the lives of her patients. And Hüller played a director who was making a film about a troubled relationship that mirrored aspects of her own troubled relationship, and that starred her duplicitous partner. What is the line that separates truth from fiction?

May December—January 18, 2024, 6:30 pm @ the Film House

Todd Haynes burst onto the film scene in 1987 with his underground classic Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, whose odd but fascinating delivery was part camp (the drama was acted out with the use of Barbie dolls), part music film (The Carpenters and the soft rock revolution they helped pioneer, and part family melodrama (with a considerable amount of tragedy, given the story in question and Karen Carpenter’s terrible demise).

Since then Haynes has continued to return to music film with regularity, as evidenced by such films as The Velvet Goldmine (1998), on Glam Rock in the 1970s, I’m Not There (2007), his phantasmagoric study of the Bob Dylan phenomenon of the 1960s an 1970s, and The Velvet Underground (2021), his definitive documentary on the legendary underground art rock band of the same name.

But there’s little question that Haynes’s primary fixation has been with creating unorthodox variations on the family melodrama, and his mastery of this form has resulted in most of his most notable projects: Poison (1991), his first feature-length cause célèbre; Safe (1995), his first collaboration with the great Julianne Moore; Far From Heaven (2002), his tribute to Douglas Sirk and especially All That Heaven Allows (1954), and his second collaboration with Moore; Mildred Pierce (2011), his inspired mini-series version of the noir classic, starring Kate Winslet; and Carol (2015), his mesmerizing, award-winning adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, “a modern novel of two women.”

Now Haynes is back with May December another utterly bewitching and highly unconventional family melodrama, this one set in contemporary coastal Georgia. This time it’s based on a story ripped from the tabloids (the Mary Kay Letourneau sex scandal of the late 1990s and early 2000s), but Haynes has taken this material and transformed it into a captivating hall of mirrors. Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman star, and, as the film’s poster suggests, and as one critic has put it, “it’s a little as if Ingmar Bergman’s Persona had been remade by the Real Housewives of Savannah.”

The Pigeon Tunnel—December 7, 2023, 7:00 pm @ the Film House

This week we’ll be screening the latest documentary by Errol Morris, easily one of the most accomplished nonfiction filmmakers of the 50 years. Morris began his career in film as an upstart and an outsider, one who brought a very unorthodox approach to documentary representation on early films like Gates of Heaven (1978) and Vernon, Florida (1981). His sensibility was darkly ironic, and he displayed a knack for finding quirky characters, but his real gift was that he was unusually good at conducting interviews.* Since then, his best projects— films like The Thin Blue Line (1988), Mr. Death (1999), Standard Operating Procedure (2008),Tabloid (2010), and the series Wormwood (2017)—have all been showcases of his masterful skill with interviews. In fact, a number of these films have seen Morris go toe-to-toe with particularly tricky interview subjects—figures of historical importance known for their slipperiness and their dissembling, like Robert McNamara in The Fog of War (2003) and Donald Rumsfeld in The Unknown Known (2013).

The Pigeon Tunnel is another such interview showcase. Here, Morris’s subject is David Cornwell, the ex-British spy turned master of the spy novel, who was better known by his nom de plume John le Carré. Le Carré is best known for the clarity and brilliance of his insight into the murky and labyrinthine world of Cold War espionage, as well as the impeccable British irony and reserve he brought to the genre in such works as The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963), Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), and Smiley’s People (1979). When the Cold War ended, Le Carré somehow found a way to adapt and even flourish, as evidenced by The Tailor of Panama (1996) and The Constant Gardener (2001). Many of these novels have been adapted into memorable films, with The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1965), starring Richard Burton, The Constant Gardener (2005), with Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz, and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), featuring Gary Oldman, being particular standouts.

As the title suggests, Morris’s film is based on Le Carré’s utterly fascinating 2016 memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories From My Life. David Cornwell died in 2020 at the age of 89. Morris was lucky enough to have gotten the opportunity to interview Cornwell at length just before he died. And now we’re lucky enough to have Morris’s film on the great John le Carré.

*As a PhD student in his twenties, Morris prided himself on being able to get an interview subject to fill both sides of a 120-minute audiocassette (remember those?) with the rambling, revealing answer to just a single question or two.

Rush to Judgment—November 22, 2023, 7:00 pm @ the Film House

Wednesday, November 22, 2023 marks the 60th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. To commemorate this solemn occasion, the Film House together with the Brock University Film Society will be showing a new 4K restoration of Emile de Antonio’s 1967 documentary Rush to Judgment, the first important film to address the President’s murder and to call the conclusions of the the Warren Commission Report (1964) into question.

As the title suggests, the film was based on Mark Lane’s book of the same name, which had been released a year earlier to great acclaim—and great controversy—and Lane is a major figure in the film, leading its inquiry. Lane’s Rush to Judgment (1966) was the first mass-market book to raise serious doubts about the Warren Commission, and to investigate the murders of John F. Kennedy, Lee Harvey Oswald, and Officer J.D. Tippit of the Dallas Police Department, who Oswald was also accused of having murdered during the same crime spree. Though it had been preceded by a number of self-published books on the topic, Lane’s book had a certain weight to it. Lane was a lawyer and former New York State legislator, one who had represented the Oswald family before the Warren Commission out of concerns that the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office had botched the investigation, and, therefore, he was particularly well-versed in the details of the case. His book was published by Holt, Rinehart & Winston, and it came with an introduction by Hugh Trevor-Roper, a distinguished Professor of History at Oxford University.

De Antonio was a maverick documentary filmmaker whose first film, Point of Order! (1964) was a brilliant indictment of McCarthyism and 1950s anti-communist fear mongering constructed entirely out of archival materials. He would go on to make such celebrated documentaries as In The Year of the Pig (1968), the first feature-length film to explore America’s involvement in Vietnam in depth and to construct a powerful argument against the war, and Millhouse: A White Comedy (1971), a trenchant critique of Richard Milhous Nixon that was produced and released during Nixon’s first term, years before news of the Watergate scandal went public.

De Antonio’s Rush to Judgment is a crucial artifact from the period immediately after the assassination of the President, and just a year before the assassination of his brother, Robert F. Kennedy, who was running for president at the time. It features interviews with numerous first-hand witnesses of the attack on the Presidential motorcade, including Abraham Zapruder, the businessman and amateur filmmaker whose 8mm record of the assassination remains one of the most heavily scrutinized and widely discussed pieces of celluloid ever filmed. After years where Rush to Judgment languished in obscurity due to poor distribution, de Antonio’s bracing documentary has been digitally remastered so it can raise questions anew about this “murder most foul.”

Please join us for this special screening. After the screening, there will be a discussion of the film led by myself and Dr. Barry Grant.

The Killer—November 9, 2023, 7:00 pm @ the Film House

David Fincher has always been a director of bold visual style. He’s best known for films like Fight Club (1999), Panic Room (2002), The Social Network (2010), The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2011), and Gone Girl (2014), but he got his start directing music videos in the 1980s, including such icons of pop and postmodernism as Madonna’s “Express Yourself” (1989) and “Vogue” (1990), so he’s very much a product of the MTV Generation.

Of course, Fincher is also know for his stylish, yet macabre fascination with serial killers, as exemplified by films like Se7en (1995) and Zodiac (2007), and the television series Mindhunter (2017-9), all of which delve deep into efforts to investigate, study, and come to terms with the psychology of serial murderers. Which is one of the reasons this latest project is so interesting.

Here, with The Killer, Fincher has turned his attention to the mind of another kind of serial killer: a paid one, a professional assassin. Michael Fassbender plays a high-calibre contract killer whose complicated psychology and brazen amorality are under scrutiny in a tale of double-crossing and retribution that is reminiscent of such classics of the genre as Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967) and Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog (1999). Did I mention The Killer is “wickedly funny,” too? More than one critic has mentioned how incredibly entertaining the film is.

In the end, it all boils down to that distinctive Fincher aesthetic, though. As Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian puts it: “This is a thriller of pure surface and style, managed with terrific flair.”

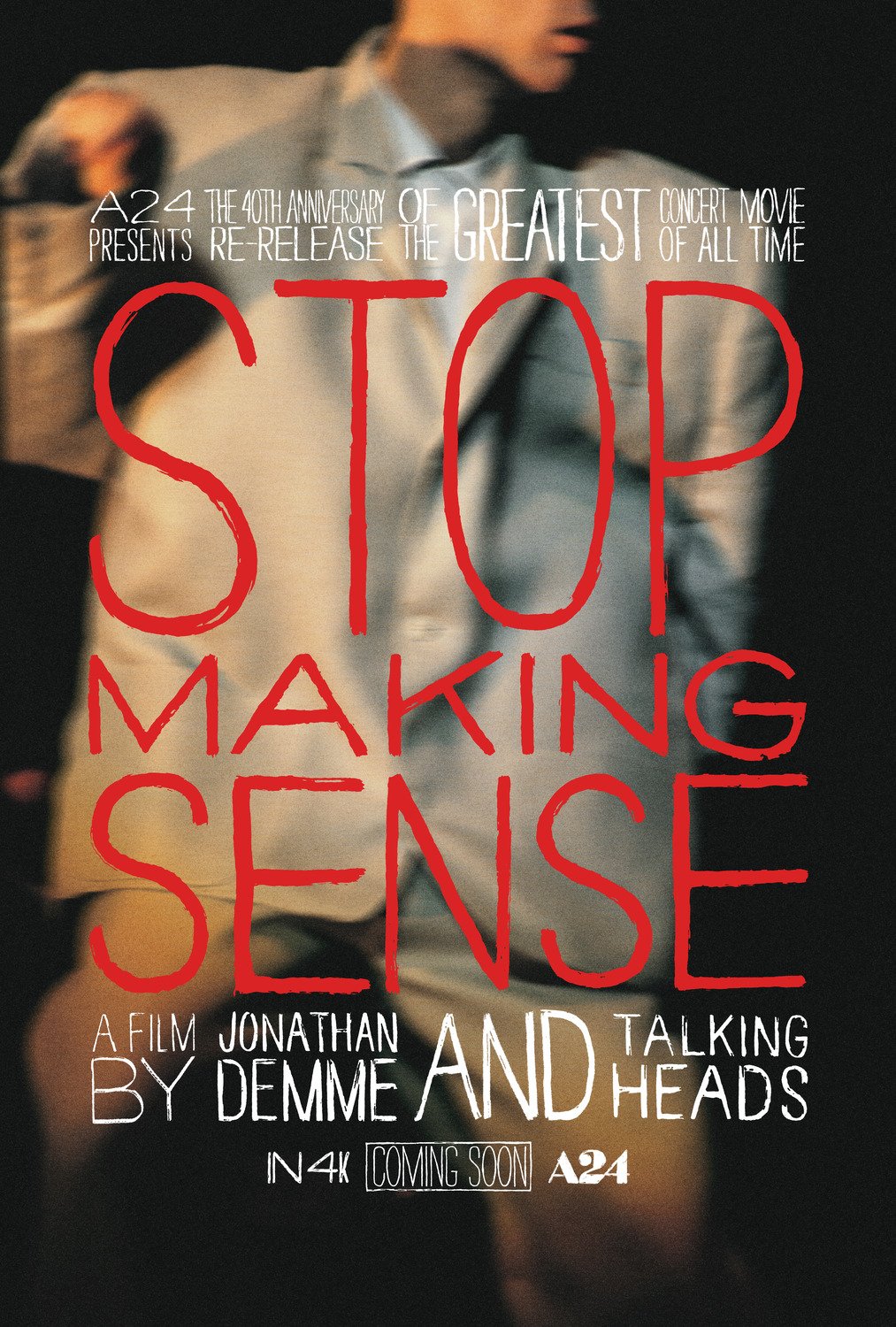

Stop Making Sense—October 22, 2023, 7:00 pm @ The Film House

By 1983, Jonathan Demme was a promising director who had been working in the industry for about a decade but had yet to hit full stride. He was on the verge of becoming an indie darling with a knack for using hip New Wave-fuelled soundtracks to full effect, as he did with Something Wild (1986) and Married to the Mob (1988), but his blockbusters of the ‘90s (The Silence of the Lambs [1991] and Philadelphia [1993]) were still beyond reach. The film that stands as the major pivot point in Demme’s career was his first documentary, and, more importantly, his first rockumentary: Stop Making Sense (1984).

Here, a talented and aspiring director teamed up with the band Talking Heads at the peak of their powers and at the height of their artistic ambitions, and the result of this most fortuitous cinematic alchemy was (yes, you guessed it!) pure gold. Together, Demme and David Byrne, the band’s singer, lyricist, and resident performance artist, deconstructed the concert film, stripping it of its clichés and excesses (e.g., The Song Remains the Same [1976]). Then, with his bandmates Tina Weymouth (bass), Jerry Harrison (keyboards and guitar), and Chris Frantz (drums), plus an expanded lineup that included such luminaries as Bernie Worrell (Parliament-Funkadelic), Byrne and Demme reconstructed the concert film as something both mysterious and mesmerizing, an utterly irrepressible, totally irresistible, hyper-kinetic experience. As Roger Ebert once put it, “The overwhelming impression throughout Stop Making Sense is of enormous energy, of life being lived at a joyous high.”

From this point on, Demme became known for his taste in music, as well as his genius for capturing it on film. He made a large number of rockumentaries in the years to follow, as well as many music videos, and he developed lasting relationships with such icons as Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen. But it’s safe to say that he never achieved the heights of Stop Making Sense ever again. It’s not clear anyone has.

The concerts immortalized in Stop Making Sense occurred in Hollywood in December 1983. This Sunday we’ll be holding a special Sunday Meeting edition of the Brock University Film Society featuring a brand-new 4K restoration of the film just in time for its 40th anniversary. Take Me to the River! (And don’t forget your dancing shoes!)

Searching for Sugar Man—September 14, 2023, 7:00 pm @ The Film House

Hello, everyone,

That's right—it's that time of year again! We'll be kicking off our BUFS 2023-2024 season tomorrow, Thursday, September 14, with a special presentation of Malik Bendjelloul's 2012 film Searching for Sugar Man, his documentary on the mysterious life and the remarkable impact of Sixto Rodriguez. This supremely talented musician and songwriter from Detroit died in early August at the age of 81, and the news came as something of a shock for those of us who are fans—rumors of his death had dogged the enigmatic performer for decades. Searching for Sugar Man won the Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary in 2013, one of only a handful of music documentaries to have done so,* but this film is quite unlike most other rockumentaries--there are so many unexpected twists and turns to this story.

If you've had the pleasure of having seen Searching for Sugar Man in the past, here is your opportunity to revisit the film and pay tribute to the man once again. If you've never seen Searching for Sugar Man, you (and your students) are in for a treat!

*For those who are curious, the other films in this elite group are Brigitte Berman’s Artie Shaw: Time is All You’ve Got (1985), Morgan Neville’s Twenty Feet from Stardom (2013), Asif Kapadia’s Amy (2015), and Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson's Summer of Soul (2021).