This post documented our 2013 holiday bash, which, as you will read below, did NOT take place at AEB HQ. It had to be moved at the last minute due to an unexpected crisis. Luckily, a dear friend stepped in to help us out. We changed the location and sent out revised invites, and the party ended up being a hit. (TY, RD! I’m still blown away by your generosity.) Anyway, it’s a nice story and it contains a great go-to recipe: Off-Oven Roast Beef. That recipe is the reason we decided to revisit this post. It will be the centrepiece of our Christmas Eve dinner this year. Can’t wait! It always works like a charm!

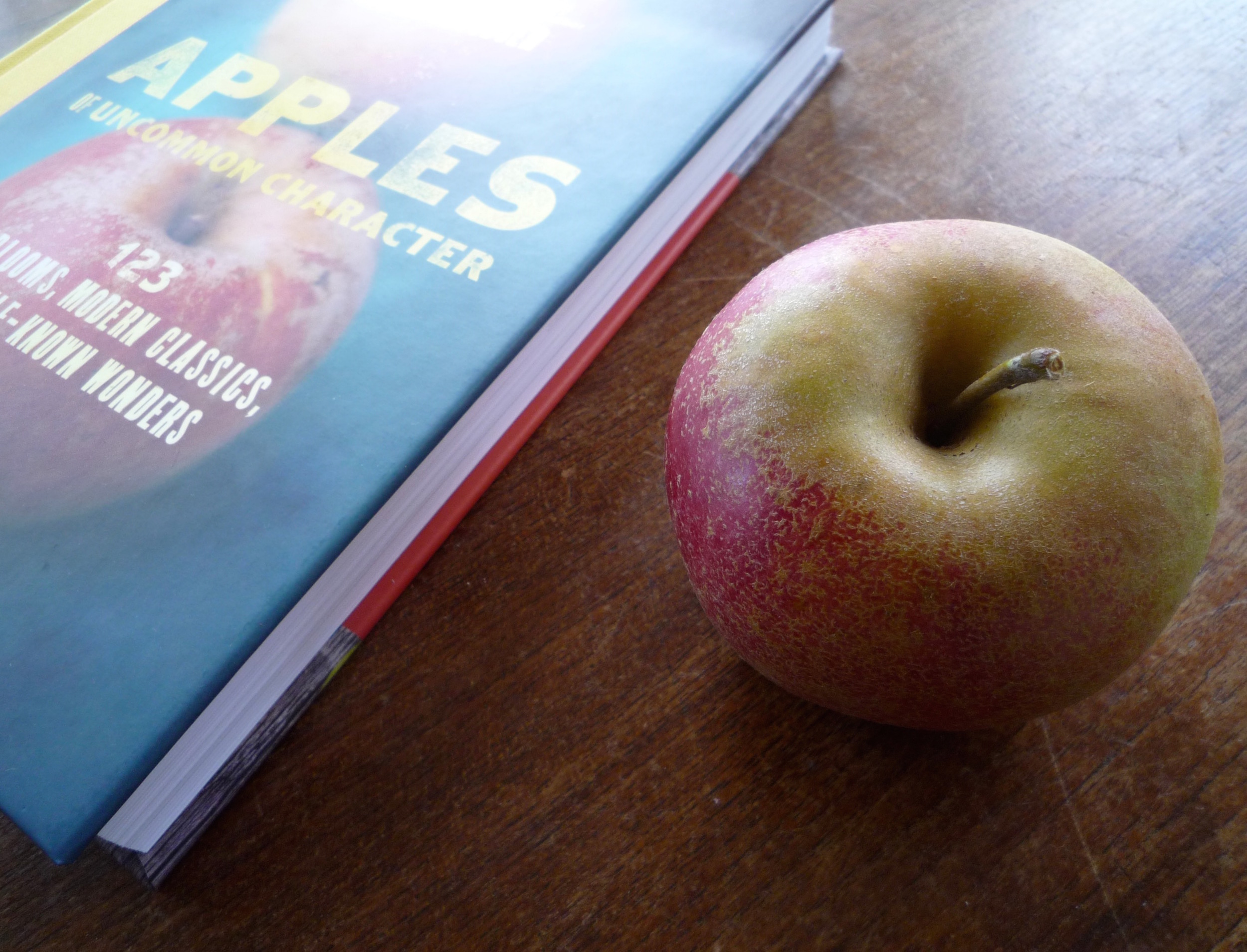

fig. a: holidaze 2013

We hold these truths to be self-evident:

1. The holiday season is upon us.

2. Good God, there's nothing like a perfectly seasoned, perfectly rosé slab of roast beef--preferably one that's then sliced extra-thin, and served with horseradish.*

Okay. Yes, the holidays are here. And that means it was time for our annual "...an endless banquet" Christmas spectacular.

fig. b: all aboard!

But, the thing is, sometimes LIFE confronts you with an unexpected storm, and, suddenly, you have to chart a new course.

That's kind of what happened this year. Everything's fine now, there's no need to worry, but something came up that forced us to make a last-minute adjustment. What it meant was that the Christmas spectacular didn't actually take place at our place this year. Consequently, we toned things down a bit, scaled things back, and got "back to the basics."

The holiday bash that resulted might not have been quite as wide open as it had been in the past, it might not have been quite as extravagant, but it was still pretty spectacular, and it was much more of a collaborative effort--and all the better for it. For all these things, we owe our undying gratitude to our hostess. (TY, RD!) Such a lovely apartment, such a wonderful atmosphere, such a great time!!

fig. c: Shamrock!

Originally, we'd come up with this vague Lake Champlain "holiday steamship" theme. The "point of departure" was meant to be our apartment. I guess we ended up docking just a little ways up the coast. And we exchanged the S.S. Champlain for the S.S. Shamrock.

Did I mention that there was a pretty significant snowstorm the day of the party? No big deal. We're Montrealers, we know how to deal with such situations.

Anyway, "back to basics" meant simpler preparations. It also meant fewer last-minute preparations. But it was still pretty plentiful. The spread:

fig. d: rye!

1 spiral-cut, cob-smoked, maple-glazed Vermont ham with mostarda cherries

1 roast beef with horseradish

nordic shrimp salad

smoked trout & smoked sturgeon platter with cream cheese

crudités & herb dip

baked artichoke dip & corn chips

cheese platter (featuring 1 Jasper Hill Moses Sleeper + 1 Shelburne Farms cloth-bound cheddar)

freshly baked Danish rye & corn rye loaves

Spanish clementines

gingerbread cookies

festive fudge

AEB rum punch

aged egg nog

fig. e: festive fudge!

And, yes, getting back to that point #2: a perfectly executed roast beef is a thing of beauty. It also seemed like just the kind of thing that would have been served in the dining room of an elegant steamship back in the day.

We discovered a method for a simple roast beef that we really love--and that's proven to be foolproof--earlier this year in the pages of The New York Times. The recipe accompanied an article on Louisville's enigmatic Henry Bain sauce. Though the sauce was designed to be served as a condiment with everything from steaks to game, it's a stone-cold natural with roast beef. In fact, Sam Sifton claimed that this may be the sauce's "highest use" in his article, so he turned to Tyler Kord, the sandwich master at New York's No. 7 Sub, for a killer roast beef recipe to go along with his recipe for Henry Bain. And that's exactly what he got. I liked the recipe for Henry Bain--it was definitely unlike anything I'd ever tasted before, and, it's true, it made for a tasty accompaniment--but I absolutely loved the recipe for that roast beef.

As many of your probably know already, getting perfect results with roast beef can be a little tricky. Nobody likes a roast that's extremely undercooked, and overcooking a roast is all too easy. This recipe relies primarily on ambient heat to gently warm the roast all the way to its centre, resulting in that ideal rosy hue, not to mention an extremely savoury crust, optimal juiciness, and some outrageous pan juices.

I've been impressed with Kord's recipe since the first time I tried it, but recently I made an adjustment to it that's even more to my liking: I added ground caraway seeds to its spicy-garlicky rub, giving it a finish that was very much in tune with the nordic characteristics of our Christmas party spread.

Off-Oven Roast Beef

1 beef roast, like top, eye or bottom round, approximately 3 lbs

1 tbsp kosher salt

1 tbsp freshly ground black pepper

1/2 tbsp freshly ground caraway seeds

3 cloves garlic, peeled and minced

1 tbsp olive oil

red pepper flakes to taste

prepared horseradish or horseradish cream

Remove the roast from the refrigerator.

fig. f: raw!

In a small bowl, mix together the salt, pepper, caraway seeds, garlic, olive oil and red pepper flakes to create a paste. Rub this all over the roast.

fig. g: rubbed!

Place the roast in a cast-iron skillet or roasting pan, fat side up, and allow the roast to come to room temperature, about 1 to 2 hours.

About 15 minutes before you want to begin roasting, preheat your oven to 500º F.

Place the roast in the oven. Cook, undisturbed, for 5 minutes per pound. [I tend to go a little over this recommendation: e.g. 15 minutes for a 2.6-lb roast, and 30 minutes for 5.25-lb roast.]

Turn off the oven. Do not open the oven door. Leave roast to continue cooking, completely undisturbed, for two hours.

After the two hours is up, remove the roast from the oven. Slice as thinly as possible.

fig. h: roasted!

Serve with pan juices and prepared horseradish. Or use to make whatever your preferred kind of roast beef sandwich is.

[recipe based very closely on Tyler Kord's Off-Oven Roast Beef recipe, as featured in The New York Times, January 17, 2013]

Just how good is this roast beef? Well, the photos above are of the 2 3/4-lb roast we made the day after we made a 5 1/2-lb roast for our party--a 5 1/2-lb roast that completely disappeared (as tasty things often do). You see, the next day we found ourselves still having major roast beef cravings, so I went out and picked up another roast and we whipped up another batch--this one served with roasted broccoli and a mixed greens salad. And horseradish, of course.

The point is: this recipe is a keeper any time of year, but it's great for the holidays. Great for a party spread. Great for pleasing a crowd. Great for making sandwiches.

Happy holidaze 2023! Eat well! Drink well! Be well!

aj

*Actually, roast beef's a pretty lovely thing to serve with radishes à la crème, too. In fact, the two combined would make for a pretty amazing open-faced roast beef sandwich. Just a thought...