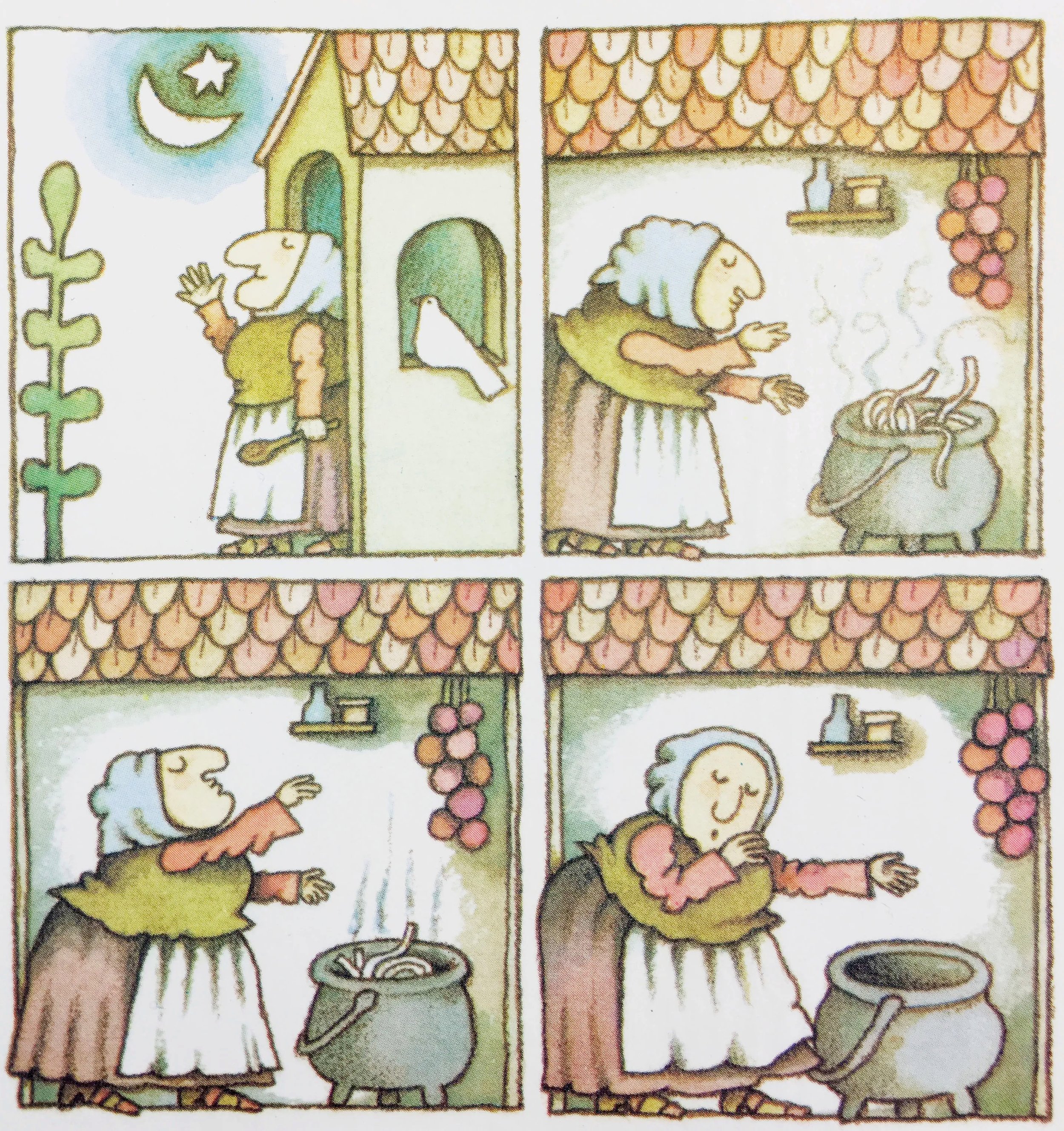

fig. a: Ungarisch bean soup

Is this a classic Hungarian Csülkös Bableves? Well, not exactly. But it’s true to the spirit of one, minus the ham hock. Not that I have anything against a ham hock. Nor do I have anything against roux, which most bableves recipes use to thicken the soup. But if you can’t find a good ham hock, you’re okay with a Hungarian-style bean soup that’s entirely vegetarian (actually, hold off on that dollop of sour cream and it’s vegan!), and the roux seems like overkill, just make sure to use quality dried white beans and the finest paprika you can find and you should end up with a beautifully creamy, delicious, and supremely warming bean soup in the Hungarian style. Hence, “Ungarisch,” the German word for Hungarian, which conveniently comes with the -ish, or rather the -isch, built in.

Ungarisch Bean Soup

1 lb thin-skinned dried white beans (such as Rancho Gordo’s fabulous Marcella beans)

2 tbsp olive oil

I medium yellow onion

2-3 green or yellow peppers, preferably Hungarian banana peppers or Cubanelles

1 jalapeño pepper (if using 2 Cubanelle peppers)

2 carrots, peeled and chopped

1 stalk celery, chopped

1 tbsp tomato paste, preferably Italian concentrated

1 rounded tbsp sweet paprika

1/2 tbsp smoked paprika, preferably spicy

Salt & freshly ground black pepper

Sour cream (to serve)

Rye bread (to serve)

Use the quick-soaking method to prepare your beans.

Cook the beans until blowing on them the way you might blow out a candle splits the skin. Set aside.

Pre-heat your oven to 300º F.

In a Dutch oven, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the the onion and sauté until translucent. Add peppers, carrots, and celery, and continue sautéing until softened. You might want to add some salt to help with this process.

When the vegetable mixture is softened, and the tomato paste and sauté for another minute or two. Add the paprika and sauté for another minute.

Add the reserved beans with enough bean liquid to cover by an inch.

Bring the bean soup to a rolling boil. Turn the heat down to low and cover. If your oven is at temperature, move your Dutch oven into the oven and bake for 90 minutes, covered.

After 90 minutes, check on your beans. They should still be on the firm side. Taste your bean broth. Add salt and freshly black pepper to taste.

Return the Dutch oven into the oven and bake for another 60-90 minutes, covered. If the beans were bubbling wildly when you took them out of the oven, turn the oven down to 275º F.

After 60-90 minutes, check the beans again. If they are still too firm, put them back in the oven for another 30 minutes. Adjust the seasoning.

When the beans are ready (creamy, flavourful, luxurious), ladle the soup into bowls. Serve with a dollop of sour cream (if you’re a fan), and a slice of rye bread (preferably homemade—you know, like this)

fig. b: rye bread

with butter, of course.

Enjoy!

Serves many. Makes them happy.

aj