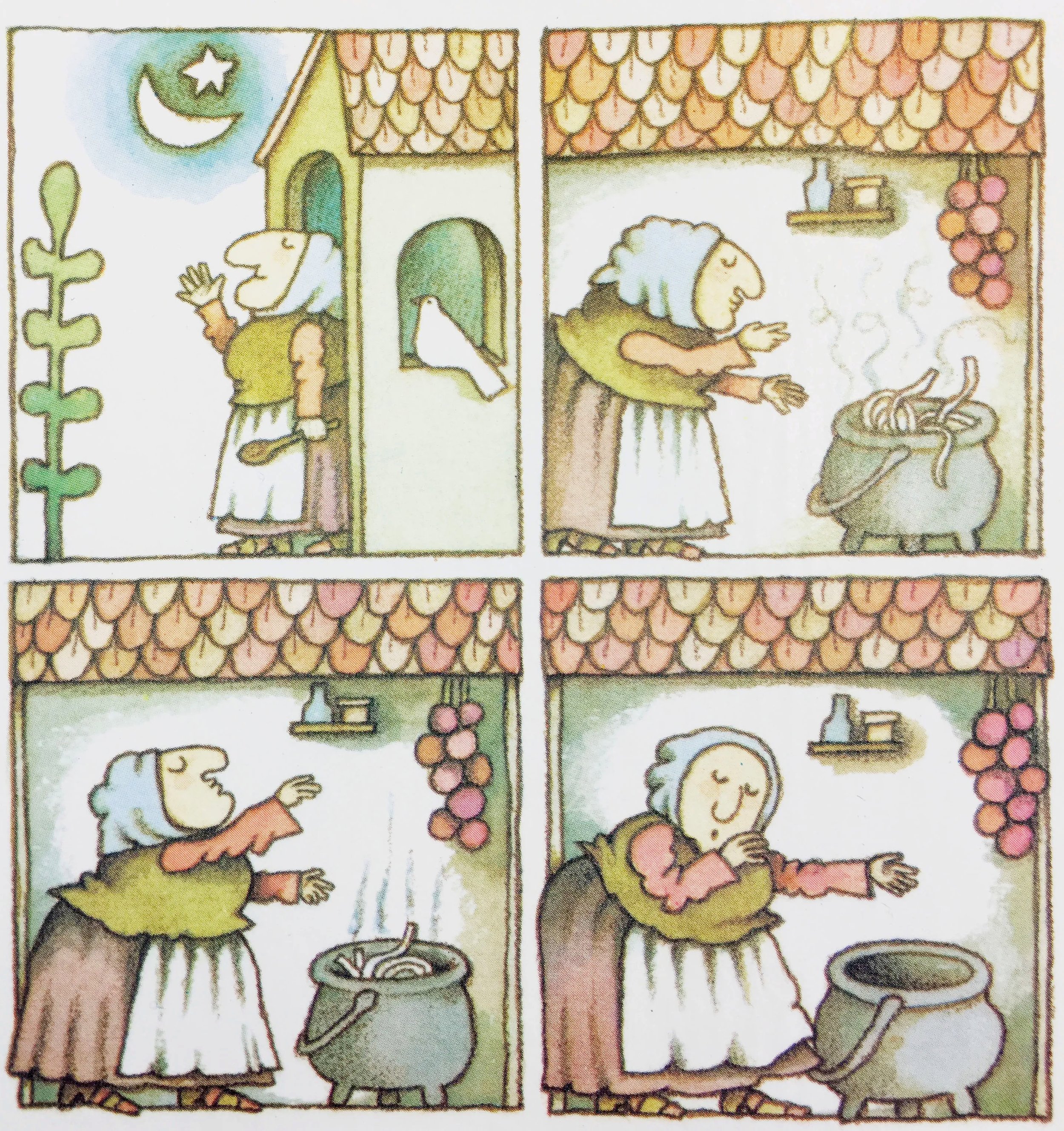

When we were kids, my sister and I were fans of Tomie dePaola’s Strega Nona. Who wasn’t back then? Back in the freewheelin’ '70s. Back before the conservative movement had launched its Inquisition to purge children’s literature of anything that might not be in step with its radical Christian fundamentalism. Back before even Strega Nona came under scrutiny. The book had just won a Caldecott Medal and had quickly become a beloved classic of children’s libraries across America. Of course, I had extra reason to be on board—Strega Nona’s assistant was a guy who went by the name of Big Anthony. Cool handle, right?

fig. a: Nona & Tony

Anyway, recently I found myself thinking about good ole Strega Nona and her witchy ways again for the first time in ages when I came across a tantalizing, revelatory recipe. Why Strega Nona?

fig. b: Nona knows best

Well, it had something to do with the fact that it was a pasta dish that came with a “colourful” Southern Italian name, not unlike Strega Nona (basically “Grandma Witch”). Plus, you don’t need spells or a magic pasta pot to make it, but the dish is rather magical.

The recipe in question was for Rigatoni alla Disgraziata—”the poor wretch’s rigatoni.” (You’ll notice that, as they always are, this pasta dish is gendered feminine, so the “poor wretch” in question is a woman. That didn’t stop me from identifying with her. I mean, Big Anthony didn’t have any hesitations about hanging out with Strega Nona, did he?) The dish is a classic of the Sicilian repertoire, but I’d be surprised if variations aren’t also found in other parts of Southern Italy (like Calabria, Strega Nona’s home region), because it’s basically a simple, honest, and satisfying eggplant pasta dish, a “peasant’s dish,” a prime example of cucina povera. This particular version involves some cheese, but the breadcrumbs that are essential to its preparation would often be used as a substitute for cheese in poorer households. The two vegetables necessary to make the dish are eggplant and tomatoes, staples that virtually every Sicilian family would have had on hand (or would have easily been able to access, one way or another).

fig. c: eggplant & tomatoes

Use the best eggplants and tomatoes you can find—preferably out of your own garden—but the bottom line is this is cucina povera—the cuisine of the poor and of the frugal—use what you have. In my case, I found some gorgeous organic eggplant at the market, but I wasn’t so lucky with tomatoes, so I made do with canned ones.

And while the recipe that I used as a model was for rigatoni, I substituted in busiata instead, because that’s what I had on hand, because they hail from Sicily (Trapani and environs in Western Siciliy, to be specific, where they’re often used to make Busiate alla Trapanese), and because their worm-like shape seemed appropriate to the dish in question (and ideal for the lead-up to Hallowe’en).

figs. d & e: Busiata di Sicilia

My source was a beaten-up old copy of Saveur Cooks Authentic Italian (2001), from the heyday of the beloved magazine. It’s amazing what turns up again when you move, as I did recently, and it’s amazing how well a good cookbook (just like a good children’s book) stands the test of time. Now that my knowledge of Italian cuisine has expanded, now that I’ve spent a little bit more time in Italy, this collection of recipes seems even more vital than it did in the early 2000s. Its cucina povera game was always strong, however, something which was a distinct bonus back when I was a graduate student and which always endeared me to it. Why I’d never tried making Rigatoni alla Disgraziata is a mystery to me.

The technique that’s featured here and that I found “revelatory” is a simple one for preparing eggplant. Eggplant is famously difficult for so many home cooks who don’t come from a tradition of preparing, consuming, and enjoying eggplant. Sure, you’ve read that certain eggplant dishes are considered the pinnacle of vegetable cookery throughout the the Mediterranean region and beyond, but the issue of even choosing nice eggplants can be daunting for many, let alone transforming them into something majestic. And god knows improperly cooked eggplant is a horror.

In this case, I started with Japanese-style eggplants, which are often a safer bet than larger globe eggplants because they’re less seedy and they cook up quicker. The fact that these were local and organic and that I had great faith in the farm that raised them made them an even better bet.

Cubing the eggplants, generously salting and tossing the cubes in a colander, and allowing them to “sweat” for an hour or so is a standard method for removing the bitterness of untreated eggplant. Many recipes that involve Japanese eggplant don’t call for this step, but you still may want to go this route just to be sure (I did).

But the genius of the recipe has to do with pan-frying the eggplant in a generous amount of olive oil before it gets anywhere near a sauce. The idea is to transform the cubes into golden little jewels of flavour that are lightly crispy on the outside and positively melty inside. By the time this step is completed, the eggplant is already delicious, but it’s ready to become even more so when tossed with your sauce, your pasta, and your cheese.

This technique is useful in a wide range of contexts and recipes. For instance, Michelle has been using a variation on this technique (she chops the eggplants differently and cooks them in a different type of oil) for some of her Japanese dishes for years. Like I said, once you’ve prepared the eggplant in this manner and seasoned them, they’re already delicious, anything else you do to them is extra.

But in this case, the eggplant formed the basis of a rustic pasta dish:

Busiate alla Disgraziata

3-5 small Japanese eggplants, or 2 medium globe eggplants, trimmed and cut into cubes

Kosher salt

1/2 cup plus 2 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil

1 cup fresh bread crumbs

1 lb busiata or rigatoni

1/4 tsp red pepper flakes

2 cups tomato sauce, preferably homemade

1/4 cup grated pecorino or ricotta salata

freshly grated Pamegiano-Reggiano

Put the eggplant in a colander, sprinkle liberally with salt, and toss to coat well. Allow to drain for 1 hour to “sweat” and extract bitterness. Rinse the eggplant and pat dry with a clean kitchen towel or paper towel.

Heat 2 tbsp of olive oil in a large, heavy skillet (I used a 10” cast-iron one) over medium-high heat. Add bread crumbs and cook, stirring, until golden, about 2-3 minutes. Transfer to a bowl and set aside.

Wipe out the skillet with paper towel, add remaining 1/2 cup* olive oil, and re-heat over medium-high heat. Add half the eggplant and cook, stirring and flipping the cubes often, until golden, 8-10 minutes. Transfer eggplant with a slotted spoon to a large bowl and season to taste with salt. Repeat process with remaining eggplant.

Cook past in a large pot of boiling generously salted water until al dente. Add red pepper flakes to tomato sauce in a small pot and warm over medium heat, 4-5 minutes. Drain pasta in a colander and add to bowl with eggplant. Add tomato sauce, pecorino or ricotta salata, and bread crumbs and toss well.

Serve sprinkled with Parmigiano Reggiano, accompanied with a glass of red wine, some chili oil, and a green salad.

[Based very closely on a recipe from Saveur Cooks Authentic Italian (2001), by the Editors of Saveur Magazine]

The final product should look something like this:

fig. f: Busiate alla Disgraziata

I found it deeply satisfying, perfect for the late harvest season, and not a disgrace in the least. Quite the contrary. To me it’s quite beautiful, and I wish I had a magic pasta pot that was capable of producing vast quantities of this utterly delicious dish. But even more important is the magical transformation that is at the heart of this recipe, and that blesses it with heart. Like all great cucina povera—like all great “peasant food,” in general—it’s a dish that glories in creating “something” out of “nothing”—something wonderful.

Big Anthony

Note: the original recipe calls for 1 cup of olive oil. If you’re using an even larger skillet, you may need to use more olive oil than I did—up to 1 cup. But for a 10” skillet, I found 1/2 cup was ideal.